The Destroyer of Worlds

Philosophy

Politics/Social Commentary

Aug 2015

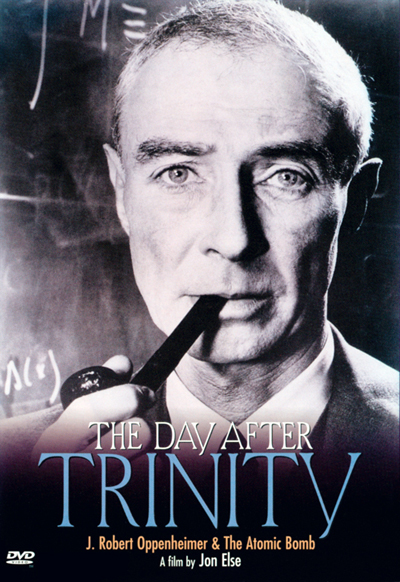

One of the years I was studying at Florida State, I taught a History and Philosophy of Science class based around film. Each week we would discuss how a certain film portrays science and its relationship to the rest of human life. This course was one of the more rewarding courses I've taught, and one film stands out as the most thought provoking and revealing: The Day After Trinity. Released in 1981, The Day After Trinity, explores the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb. He was the chief scientist on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos. The film was made after Oppenheimer's death but while many of the scientists who knew and worked with him still lived, such as his brother.

One particular scene always stands out to me. One of the scientists who worked on the bomb, Robert Serber, was sent as part of a team to investigate the damage done in Hiroshima shortly after the Japanese surrender. One question this team sought to answer was whether the bomb detonated at the target altitude above the ground. They manage to find a shadow on a wall of a schoolroom, etched by the blazing light shining through a window. From the angle that the window pane's shadow made on the wall, they were able to calculate that Little Boy did indeed detonate at the specified height. This scene stands out to me because of Serber's face as he recounts this story. He gets that schoolboy glow about him, pointing at his little piece of a schoolroom, excited to explain this clever little trick he and his team figured out. But right after he stops talking, before the scene cuts, it seems like he catches himself: his smiles fades, the glow disappears. He almost looks guilty for having given into the temptation of joy in a moment of weakness.

My mind returned to this scene several times in the past few weeks. August 6th marked the seventieth anniversary of the destruction of Hiroshima. Despite the years which separate the America then from the America now, I am still somewhat haunted by that act. It haunts me because a single species now has the power to destroy much of the life on earth. It haunts me because of the naivety of many scientists, men and women who still believe that the search for scientific knowledge can be divested of all moral claims. It haunts me because we chose a virgin target, a city untouched by our incendiary bombs, a place where thousands of civilians fled to escape the ravage of war, and we did so for the sake of measurement. It haunts me because, as I have often come to realize, Nietzsche was right: the will to truth is the will to power.

Before 2011, at the National Museum of American History there was an exhibit called Science in American Life. It was fascinating. In the tone and diction of the plaques, you could trace the debate science has been having with itself ever since we dropped that bomb: who is to blame when science is used for evil, who is to blame for technology both liberating us and destroying the very ecosystem which sustains us? Is science a disinterested search for truth, or is its very nature entwined with the scientists themselves, member of our fallible little race. As you walked through the story of how science has impacted Americans, learning about the first research laboratories, the invention of polyester by DuPont, and the beginning of the Manhattan Project, you rounded a corner and came to something very different. What follows in an excerpt from a paper I wrote in graduate school about the exhibit:

To me, the creation of atomic weapons embodies one of the most fundamental problems we humans must face about ourselves: no matter how technologically advanced we may become, we may fail in the end not because we couldn't solve the problem or invent some new, clever solution, but because we lacked character, compassion, and empathy. In the film Contact, when Jodi Foster's character is asked to pose a single question which she would ask of an advanced alien race, she responds with, how did you do it? How did you evolve and survive without driving yourselves to extinction? This is exactly the right question. Will our compassion outstrip our greed? Will the need for our species to unify for the good of all arrive before our petty quests for the accumulation of capital turn the earth into a wasteland? Will the human cost of technology grow so great that the upside down pyramid collapses before that very technology can liberate us?

The greatest minds of the twentieth century—those star students, those unparalleled geniuses, those curious little kids who asked the right questions and cared about their learning—came together in the desert. There, hundreds of savants working side by side, with access to unlimited funds, laid the groundwork for the greatest weapon of mass destruction mankind had ever seen.