Love Thy Neighbor

Politics/Social Commentary

Philosophy

May 2015

It seems so strange: how did we forgot how to talk to one another? How did we lose our sense of community, of belonging, of neighborly care? When did we start generalizing, bifurcating, and stereotyping to such a degree that only two, infinitely pliable and immensely dangerous categories remain: us and them? We now speak in nothing but glittering generalities, afraid to say or hear hard lessons built on hard evidence: "there is no insult like the truth."

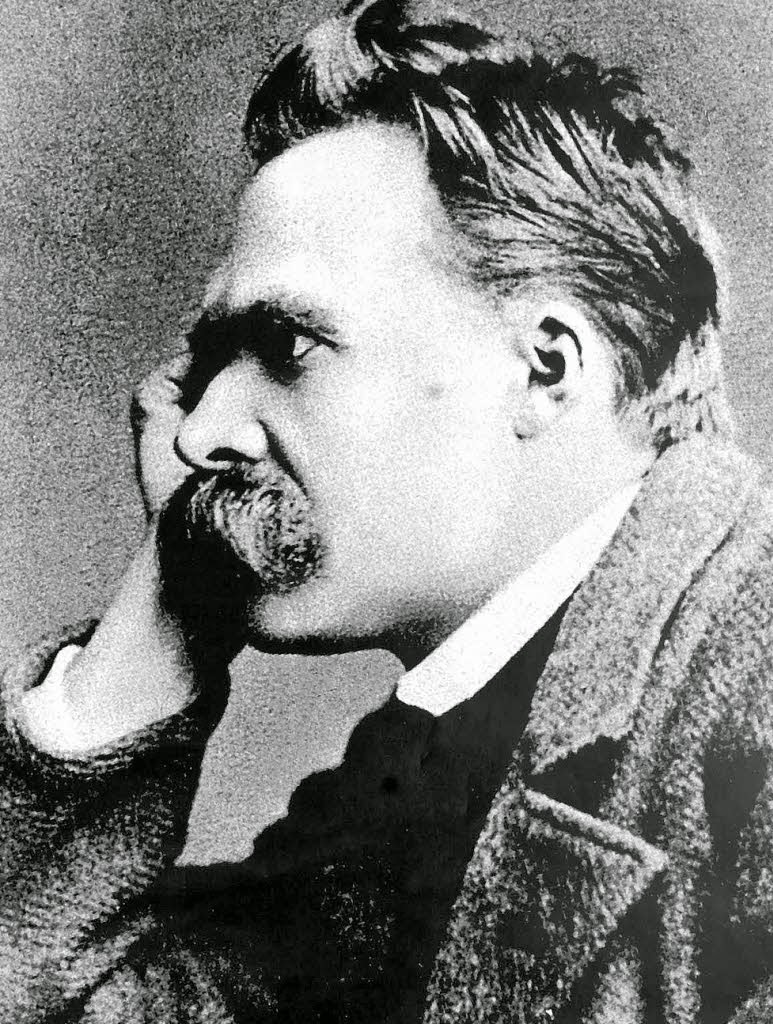

Nietzsche has a great aphorism in Beyond Good and Evil: "'Our 'neighbors' are not the ones next door to us, but rather the ones next door to them'—this is what all peoples believe." He uses a play on words here, contrasting the two different German words for neighbor, one used for "love thy neighbor" and the other for the family across the fence. I think Nietzsche hits on something crucial: it's easier to love with distance. The people right next door in our life are harder to love; it takes more work: dogs always barking, parking in the wrong spot, not mowing their lawn, playing their music too loud. You hear their fights and see into their messy living room. You know their secrets and their pain. The distant people, those neighbors whom Jesus commands us to love (in German), are faceless people, nameless people. Oh you mean people in general? Sure I love people. We are all God's children, and so on, but those bastards next door!?

But Nietzsche could have added more: it's easier to love from afar, but it's also easier to hate—and to dismiss. We've all seen the vitriol that can spill forth given the anonymity of a keyboard and computer screen. The internet has been a shot of adrenaline into the veins of our Orientialism, our tendency to group people and ideas together, the mysterious other, the savage, the third world, the emerging economy. Once categorized, we no longer need to understand them: black men, immigrants, migrants, Muslims. Our knowledge is complete. Even at home, our technology serves only to connect on the surface of our lives: phone calls have become an intrusion; text messages are better, less we step too closely to the people with whom we are communicating. In fact, a short, 140 characters, yelled at who ever is listening, must be the best way to tell the world what matters, nuance be damned.

I don't necessarily think that technology fundamentally changed us. The teenagers in my classroom aren't any more disconnected from the world than teenagers in the 50s, or teenagers in the 18th century. But I do think that our light-speed communications and incessant connectivity have brought our tendency to "other" (as a verb) out from the whispers. I think that our Facebook rants and Youtube comments teach us something about who we are, and make us long for who we could be. I don't think there was a pastoral golden age, a time when the young respected their elders, when neighbors would leave their doors unlocked instead of burning porch lights 24/7, afraid of the shadows cast by their white picket fences. We don't need to return to the good ol' days; we need to create them today.

How amazing would it be for each of us to be our selves, loyal to our deepest held beliefs, open about the opinions which separate us from fellow family members and friends, no more posturing, no more dancing around our meanings? We could approach each other with honesty and with the glue of understanding, knowing that the ties which bind us run deeper than our ephemeral states of mind and political allegiances. We could combine our labor to build a better street, a better neighborhood, a better city. We could live in a place we helped to cement with our blood and sweat, a place of which we can be proud because our very bones are a part of it. Men and women who work together, who talk together, who grow together, wield more power than any militarized police force or all the crony capitalists combined. Love thy neighbors: the easy ones, the hard ones, the ones next door, and the ones next door to them.