I am an Atheist

Religion/Atheism

Reflection

January 2015

This post has been a long time coming. Losing one's religion is a funny thing—since I grew up a Catholic among Catholics, most people in my life probably assume I'm still the same old Chad. In many ways I am, but in this one, central aspect, I have changed. I write this post mainly to clear the air, to put it all out there so that those in my life who have known me growing up can know me still. I have a hard time responding sometimes when people assume that I still attend Mass regularly, or still share their political and social views, or still pray. I want to be honest about who I am and what I think not in the hope that you'll never ask me to pray for you again, but so that when I tell you that I gladly will, you will know that what I mean is I'll be thinking about you, that I empathize with you, and that I'm here to help if I can.

I no longer consider myself Catholic. Now, to be clear, on some level anyway the mantra holds true: once a Catholic always a Catholic. I still enjoy going to Mass, mostly for the music and in the hope that the homily will be interesting and thought provoking. The Gather hymnal is burned into my bones, and I can't imagine the number of neurons in my brain dedicated to storing the lyrics of the songs within. But at this point in my life, I've left the belief in God and the Catholic worldview behind. I feel that I owe my friends and family some sort of explanation as to why, or that I should at least tell them my story. It's a bit of a long story, but I think it's worth writing down...

I've loved science for as long as I can remember. I still have my book about space facts from when I was a kid. The expanse and beauty of the universe left me with a thrilled awe; the bugs under the rocks around our house were willingly fascinating; and I always felt at home outdoors. I consider myself lucky to have been raised Catholic, part of a tradition which accepts the theories of evolution and the Big Bang, a tradition which sees no real conflict between science and religion and one which has a rich history of theology and critical thought. I don't remember ever having been confused about why Genesis talks about six days while the evidence everywhere else points towards 13.7 billion years.

The Sombrero Galaxy, a childhood favorite

Then my life was changed, as lives often are, by a teacher. She taught 10th grade biology at my high school. Under the auspices of not causing a stir, she decided not to teach us the chapter on evolution, and instead she moderated a debate between the students (I later discovered she went to the local First Baptist church and even played the angel Gabriel in one of those hell-fire and damnation plays; so perhaps she had other motivations as well). I had never really met people who thought that every word of the Bible should be taken as literally as possible. The debate boiled down to me and my close friend Tyler arguing for old Charles Darwin and a couple of students from a non-denomination church arguing for Young Earth Creationism. There was probably a smattering of Intelligent Design in there too, but that school of thought was still just becoming prominent at the time.

I dug in and started researching everything I could get my hands on. I was hooked. One of the other students invited me to hear a Creationist speak at his church and I agreed to go. I have long had a reverence for age, and when I was in high school I mostly assumed that adults knew more about the world than I did, but when I heard some of the things this man said I was astounded at how wrong it all was: it was illogical, it was unscientific, it was simply false. One particular argument that he made has stuck with me over the years. He said, "If the earth has been around as long as they say it has, there would be more dead bodies of just human ancestors than there are atoms in the universe..." I remember thinking that, while that was probably wrong, at least that had some logic to it—there can't be that many bodies because there aren't that many atoms to comprise the bodies...or something like that—but, apparently, he didn't think that was a strong enough point, so he continued, "Now tell me, if that many atoms can't fit in the universe, how could that many dead bodies fit on earth?" While my mind was busy trying to even comprehend how the hell somebody could think that this was a coherent thought, a woman behind me said, "Now that's a good point."

What?! My high school self had no idea what to think about all of this. Why were these people going through such mental gymnastics to try and force an ancient allegory into an eye witness account of the beginning of the universe? My friend managed to record the talk for me (an .mp3 I still have), and I spent a big portion of the following summer starting to transcribe it. I then went through point by point and refuted his arguments and his evidence. I only got about a third of the way through it, and at twenty pages that was a feat for a high school student over the summer. I realized that finishing was probably moot; no one at that church was going to read it, and I was too young to write something impartial. And I had half a mind to print the thing up and nail it to their church door...so I decided I should probably cool my jets.

I tell this little anecdote because I see it as the beginning of my slow exit stage left. It was the first time I really delved into how various people have tried to deal with the "science vs. religion" idea. Over the course my undergraduate days, I stayed close to the fold. I hung out at the University Catholic Center at UT. Aside from my high school friends who came to college with me, the Catholic crowd was my crowd. I went on the retreats, helped to staff the retreats, and eventually was a co-coordinator for one. I helped start a weekly discussion group focusing on Sunday's readings and spent most of my study time with my fellow Catholics. The summer before senior year I met my future wife, then a Notre Dame undergrad, at a Catholic VBS/mission trip on a Native American reservation outside of Phoenix.

After graduation I moved up to South Bend to be closer to Agata. For the second time in my life, I was spurred into really reading and researching the relationship between science and my Catholic faith. I read works from John Haught (whose God After Darwin is a must-read for anyone interested in these issues), John Polkinghorne, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and Richard Dawkins, among others. Agata and I became involved in the Communion and Liberation lay movement, and we spent hours in deep conversation between ourselves, with fellow budding intellectuals, and with professors and priests.

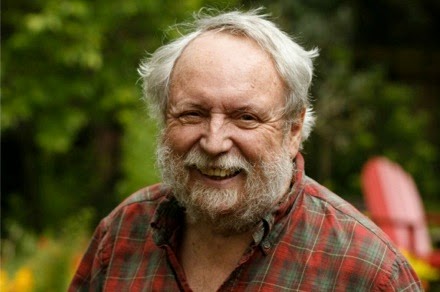

I taught high school physics for a year, but I found myself interested in graduate school. I thought about getting my Masters in Theological Studies or maybe even a Masters in Divinity. I had the good fortune to sit down with Brad Gregory for lunch to pick his brain about my future (his recent work The Unintended Reformation is interesting and causing quite a stir these days). He recommended I check out masters programs in the History and Philosophy of Science. I did and immediately decided this was what I wanted to do. I applied around and was accepted to Florida State's program, run by the philosopher of biology Michael Ruse (who first came into public prominence as an expert witness in McLean vs. Arkansas, the court case which decided Creation Science was a religion and therefore could not be taught in public schools).

Michael Ruse, the head of my History and Philosophy of Science program at FSU

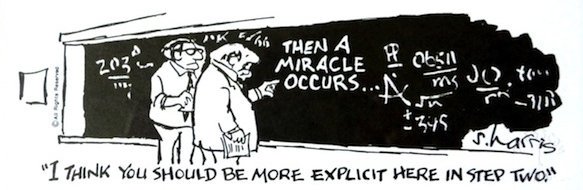

At this point, I was having serious trouble squaring the circles in my thought. I always had something of a problem accepting miracles (conservation of mass, fishes and loaves; buoyancy, walking on water), and the more I thought about it the more I decided that these stores must simply be stories, ones told to put Jesus in a context of other prophets and deities. I had recently listened to scores of lectures from The Teaching Company: Bart Ehrman on the Quest for the Historical Jesus; Jesus of the Gospels by Luke Timothy Johnson, and many others. This was my first glimpse into using the tools of historicism and contextualization to investigate the life of Jesus. Ehrman's argument that history cannot decide one way or another about miracles was interesting to me. History examines evidence and then tries to come up with the most likely explanation of that evidence. Miracles, by definition, are the least likely thing that could ever happen, so history simply cannot include them as a possible explanation of events. This doesn't mean that history claims miracles never happened, just that miracles are outside of the purview of historical evidence and research. However, and rather crucially, this lead me to realize that I had no rational reason to believe in miracles. If physics said they were impossible, and history had to remain agnostic, then what reason did I have to believe they actually occurred?

These lectures brought to light the human fingerprints all over the works found in the Bible. Being Catholic, I was never forced to deal with all of the literal contradictions in the Bible, but I still had some strong idea that the words there were somehow different than words found elsewhere. I had no idea how human the story of the Bible was. There are errors and changes which we can trace across the years, from copy to copy. Some of these changes we can tell were actually deliberate, added later to make things more coherent (e.g. the original ending to the Gospel of Mark has the women running away and telling no one that Jesus's body was missing). Others were mistakes, mistranslated words: the Septuagint—the Greek version of the Hebrew Scriptures with which Jesus and his disciples were familiar—had mistranslated the word "young girl" in Isiah to mean "virgin", which is why it was so important for the messiah to have no human father. I began to realize that in order to believe most of what I had been taught growing up, I would simply have to take the Church's word for it, which didn't sit too well with me.

Bart Ehrman, New Testament scholar at UNC Chapel Hill

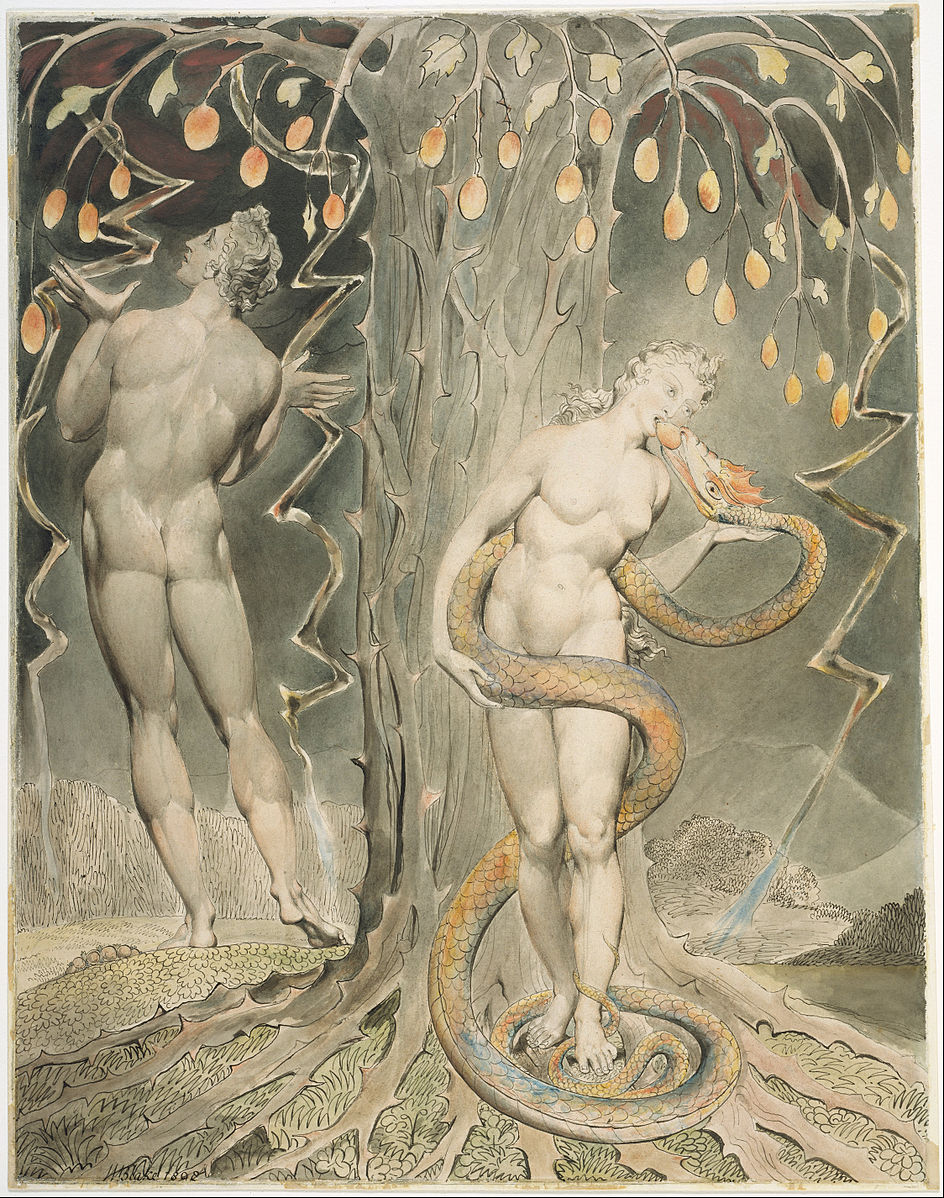

Lastly, I had just about abandoned all hope of trying to understand Original Sin or the idea of the soul. The story of Adam and Eve has long been taught as parable and allegory in the Catholic Church, but the idea of Original Sin remains crucial to the theology of the Church. While I agreed that humanity was somehow living differently than God intended (i.e. the world is far from perfect), I couldn't figure out how the fault lay in us. If evolution were really true, then the biological differences between one generation and the next are never more than those between you and your parents. But if these small differences add up over the course of millions of years, ape-like primate can evolve into us. I thought this was amazing and beautiful, but it means there was never a point in time at which we were fundamentally different than the point before it. In other words, we could not be different from the way God made us. The evil in the world, the greed, the hunger, the death, they were all there from the beginning. Why did we need salvation from them, why did this come as a human sacrifice for us? In a similar vein, if animals don't have souls, be we do (i.e we are somehow the point behind creation, made in the image of God), then when or how did this occur? Did the soul evolve too? Did one set of animal parents give birth to a soul filled child? Did God just say "bam," and all the hairless monkeys that walked on two legs were now human beings? These was probably the theological lynch pins which started the cascade. If the idea of Original Sin made no sense, then Jesus's death on the cross made no sense. Why did he need to die for us? Why did he need to be raised from the dead? From what was he saving us? From what debt or burden was he releasing us? If we have no soul, then any notion of our special role in creation, or an afterlife, was out the window.

William Blake's "The Temptation and Fall of Eve"

However, I still felt that somehow something bigger, some notion or personification of love, was behind and beneath the fabric of existence. I thought that we still existed for a reason and that there was something of an enlightenment waiting for us to obtain or find, some final secret the universe had to offer. It was amid these thoughts and questions that I moved to Tallahassee to begin my postgraduate studies.

The History and Philosophy of Science program at FSU is something of a build-your-own-masters program. The program is equally housed by the History, Religion, and Philosophy Departments. Students are given significant freedom to specialize in one of these fields. This is one of the reasons I had chosen it. I could learn about the history and philosophy of science while simultaneously divining into the academic study of religion. A perfect fit. My first semester I took the standard "Intro to the Methods and Study of Religion" course, then taught by Matthew Day.

I did well in his course (a relief, because up to this point I had specialized in physics and astronomy; I did not know if I was going to be up to snuff in the humanities), and the books I read opened an entirely new way of seeing the world. I now had a window into the social, political, and economic forces at play in our lives. Reading Durkheim, Weber, Hubert, Mauss, Levi-Strauss, Freud, Bourdieu, Marx, and many others made see realize how much of a historical being each one of us really is. The very way in which we see the world is the complex result of a myriad of historical contingencies, power struggles, and social maneuvering. What appears natural and as common sense to us, what seems special, important, or sacred, can all be understood as the result of human interactions.

Emile Durkheim

Now, to be clear, this way of viewing the sacred is not meant as an attempt to explain it away, or to discover what is really going on on some deeper level. In other words, studying religion in this manner is not a quest for the Truth behind religion. This approach, for lack of a better word, is scientific: it must have a commitment to methodological naturalism. Just as astronomy and evolution cannot appeal to miracles or a Designer, neither can the academic study of religion. There is a field where people do appeal to such a notion, but we call that Theology, and generally they have a different building. This is not to belittle Theology, rather just to describe the difference in the projects.

Now, to tie this all together. From my studies first in evolution, then in astronomy, then in the academic study of religion, I came to a point where I had adequate, natural explanations for all of the phenomena I saw around me. Life no longer seemed a miracle; it seemed inevitable. The sacred was no longer treated differently because it was sacred; rather, it was sacred because we treated it differently—the sacred was manufactured. Love no longer needed to be anchored in a far away Beyond or in an unshakable Beneath; love became an emotion which endures because it helps the species propagate. And to me, crucially, that did not diminish love. It almost felt more real, more fragile, and more worth the struggle and work needed to build a life of love between two people.

I realized that, in the end, I had no more reason to believe in God. There was nothing left in my life that I needed God in order to explain. I remember the moment. Agata and I were in the car, driving down the main stretch of road which boarders FSU. She must have been driving, because I was staring out of the side window. I didn't right then decide not to believe in God, or suddenly throw up my hands in anger or exasperation. I simply just became aware that I hadn't believed in him for some time now. In that moment I acknowledged it for the first time, let the thought turn over in my mind. I didn't feel scared or upset; actually I felt a huge relief. A burden was lifted; a deep peace settled in.

I realize that for some of you reading this, believing in God does not boil down to an explanation for something. It has more to do with faith than explanation. But to me, in my life with my experiences, faith felt like a lie. Faith felt synonymous with believing something in spite of the fact that I had no good reason to do so. I know that much has been written on faith and its nature, and that my words here sound cheap in comparison (this is no Dark Night of the Soul), but I offer them to you not as a theological treatise, only as a memoir, and emphatically not as judgment of any faith of your own.

I am glad that I grew up the way that I did. I'm grateful for what the Church gave me over the years. I have many lifelong relationships and friendships—not to mention a wife!—on account of my life as a Catholic. Like I said earlier, part of me will always be Catholic. My path is not your path; my realizations do not speak to any universal truth. Rather, my model of the cosmos fits the evidence of my personal experience. Your model fits yours. I have been in both places, and at both of those times in my life, I was right to be there.

The big concerns in life have changed from questions to answer into problems to solve. In some ways, I feel that I am more challenged to save the world as an atheist than I ever was as a Catholic. This is the only world we have, there is no cosmic justice to validate the lives lost to cruelty and greed, no one is coming to save us from ourselves. If the world is going to change it has to be us, it has to be soon. But I am grateful to the Church for teaching me to want to save the world in the first place. I am grateful for the gifts of charity, compassion, understanding, and wisdom. I am glad I was taught that the poor are blessed and that the meek shall inherit the earth. I am glad to have had a respect for ritual and for place. I am forever in debt to the sacrament of confession for giving me an outlet, a place to speak with a powerful, cleansing honesty. And most of all, I am grateful for the love of so many people, love which made me the man I am today, a love which runs deeper than doctrines and beliefs, a love which will always be here, always be yours.