Confusing Economies

Philosophy

Politics/Social Commentary

March 2014

At FSU, my professor proposed this question: what if you were invited to a dinner party and brought a relatively nice bottle of wine, something in the $25 dollar range—not too pricey but not too cheap. Then, a few weeks later, when you in turn have the couple over for dinner to your place, they bring the same bottle of wine. Why does that strike us as odd? A gift for a gift right? Or what if they bring a bottle which costs $70 instead? Or $4.99? If your return gift is too expensive, then it can be perceived as showing off or as communicating some kind dissatisfaction with the received gift. If you return too little, you don't seem to appreciate the original gift. If you return the exact same bottle of wine, or offer the $25 that it costs, you aren't giving a gift, you're paying them.

Here are some other examples, these from David Graeber. Imagine you are at a potluck dinner, and somebody is walking around with a clip board, recording all the details about what people brought and comparing it to how much food they are scooping onto their plates. Or imagine you are working on a carpentry project with some friends, and you ask one of them to pass you the hammer, to which they reply, "What will you give me for it?"

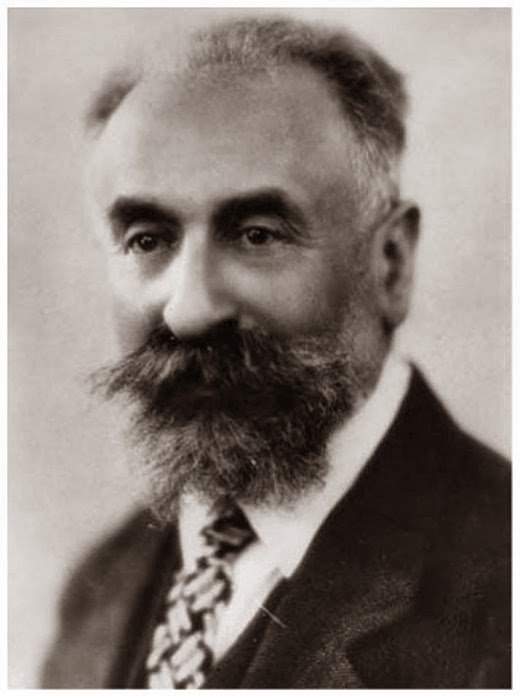

One of the classical works of sociology and anthropology is The Gift by Marcel Mauss. Mauss was the nephew and protege of Émile Durkheim (who wrote The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, one of the most influential books in the academic study of religion) and heavily influenced the founder of structural anthropology, Claude Lévi-Strauss.

The production and exchange of goods is an absolutely fundamental aspect of any human society.There are few concepts of which this could be said. The examples above highlight what Mauss and others call a gift economy. At its core, a gift economy is different than a market economy. When a gift is given, something else beyond the material is exchanged; Mauss calls it a thing's spirit, but I wouldn't go that far. There is an expectation exchanged, and there is a debt incurred. A gift obligates a gift which then obligates another gift, and the cycle continues. A social bond is nurtured by this mutual giving and returning, and that social bond can be tarnished or broken if the rules aren't followed properly.

But this isn't the case with a market. I am given an apple, and I give a dollar back. There is no social obligation for me to return and buy another, no need for the cashier to invite me out for a drink. Our exchange cuts our social bond; the relationship is ended. People don't meet in the market to make friends or to find spouses. They are there to purchase goods at the lowest possible price, and sellers are there to sell goods at the highest possible price. In the market, everyone is out for his or herself.

These aren't simply types of exchange, or types of economies; they are types of relationships. Problems arise when these two types of relationships are intermingled, one mistaken for or treated like the other. Several of the examples above are in this vein. By recording the credits and debits of a potluck dinner, one misses the point. You don't go to a pot luck to give as little as possible while maximizing your "profit". When a friend asks you hand him the hammer or to borrow it for the weekend, you just let him use it, you don't ask for collateral. Lending money to a family member is notoriously tricky. Do you charge interest? How long do they have to pay you back? What if they never do? Is it a gift now? Or do you get a collection agency involved? And what does all of this do to the relationship? The proper social place of these two different kinds of relationships is always a point of contention. The old joke about prostitutes is that you don't pay them for sex—you pay them to leave afterwards. Payment takes the place of reciprocation and ends the relationship. You don't need to cuddle or buy breakfast or talk about your future together. Money changes hands, and that's that.

Robin Williams as Mr. Keating in Dead Poets Society

Mauss wrote The Gift after he witnessed the world fall apart in World War I. Suicide rates in France were sky rocketing, birth rates were plummeting, and immigration was at an all-time high. The France which he knew seemed to be dissolving before his eyes. What was happening? At least one source of the degradation, thought Mauss, was the notion of the free gift. By insisting that a gift is free, with no obligation to reciprocate, a social imbalance is created, and social cohesion suffers.

There are many features of contemporary life which this brief discussion could elucidate (e.g. the rise of the welfare state, the link between morality and debt, the ethics of money in politics, etc.), but the one I want to highlight for now is this: the market is something different than what holds a group of people together in a community. Or rather, the market actively puts people at odds with one another, each trying to extract the most from the other while giving up the least (I will write another post sometime about why I think Adam Smith's invisible hand is not enough to save us). A crucial question for any society then must be: where do we draw the lines between market relationships and social ones? On which side of that line should we put healthcare, retirement, safety nets, or wages? Which kind of relationship should we build between neighbors? Between towns and cities? Between states or nations?

What is our relationship to the rest of society? What should we buy and what should we sell? What are we owed and what should we give? I have no ready answer to these questions, but I think that framing them this way helps to clarify what is at stake.