The Times They Are A Changin'

Philosophy

Politics/Social Commentary

November 2013

A lot of different people mean a lot of different things when they use the word "postmodern." When I use it, I tend to mean something like what Nietzsche meant by "God is dead." That is, objective Truth, perfection, utopia, or the realization of an ideal are no longer our goals in science or society. It means that there is not one answer to life's questions, not one ring to rule them all, not one all-knowing perspective, no "knowledge without a knower." Thinking along these lines has pervaded most of the liberal arts since the 1970s. It clashed with the sciences in early 90s during the so-called Science Wars, culminating in the Sokal Affair, where Professor Sokal, a physicist, managed to get a mumbo-jumbo paper published in a cultural studies journal, then announced to the world he had made the whole thing up.

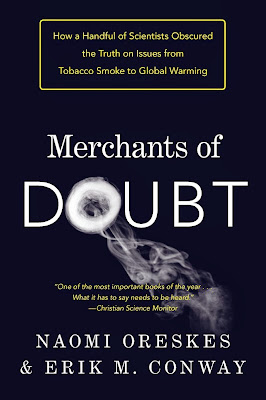

While Sokal had some good points to make, he and many scientists missed the thrust of what the postmodern critique was about. The critique is not that science is not privileged knowledge, not that science is simply one point of view among many equally valid ones. Rather, it's that science shouldn't pretend to be more than it is. Science shouldn't masquerade as the bearer of Truth. Why not? Because science, by its nature, is never, ever, 100% certain about anything. All science can do is build a model and say, based on the overwhelmingly huge amount of data we have, this is the most likely explanation, and here is what our model predicts about the future. But that does not mean science is inept, or doubtful, or "just a theory", or that we should "teach the controversy" about evolution (there isn't one). It doesn't mean that there is no actual world out there, independent of our perception of it. Science is still the best way to know anything. But we now understand that science could never have fulfilled its original, Enlightenment goal of knowing the mind of God. It means that if science acknowledges the true, imperfect nature of its knowledge, then it won't be open to attacks by those who argue that smoking doesn't cause cancer or that the climate change has nothing to do with human activity.

Some scientists have caught on. Stephen Hawking's latest book is a great example (see my earlier post for more on that). And it finally seems like the rest of society is starting to ask the right questions too. Earlier this week I posted this article from The Guardian on Facebook. It's a critique of how main stream economics is still built on the rational-actor theory, the idea that all people act rationally with perfect knowledge to achieve the best outcome for themselves. Having not learned a thing from the 2008 meltdown, economics continue business as usual. (On that note, watch Inside Job). I also posted this interview with comedian/commentator Russell Brand. Brand speaks eloquently and poignantly about the brokenness of our modern form of representative democracy, asking if it's time to try something else.

The field of education has been moving this direction stoo, despite all the of the standardized testing. We now know that not every child learns the same way, that there are many different types of intelligence, that differentiation is the key to making sure that everybody has a fair shot at success. One and the same method does not fit all our children. Standing up and lecturing while students furiously try to scribble down the important bits only works for a small minority of students.

What I'm getting at is this: it seems that, gradually, we as a society are moving away from blind, ideologically driven motivations. Quite simply, they have failed us. We are becoming more interested in data, in solving a practical problem instead of asking a big, unanswerable question, in getting our hands dirty, in not taking the easy way out to make the easy dollar. When we take off our rose colored capitalism/America/market/Freedom glasses, we begin to see that all is not well between the lines, that perhaps a form of government designed for a different age shouldn't be employed in this one, that greed will always be a part of any human system and must be accounted for and regulated against, that long term investments should be preferred to a short-sell, that, perhaps not anytime soon, perhaps not in my lifetime, but gradually, assuredly, this world is changing.